Can You See Me Running? by Bev Vincent

One of the interesting things about researching these historical context essays is that they demonstrate how unreliable memory can be. Contradictions abound. For example, depending on which account you believe, The Running Man was written either before Stephen King started Carrie or immediately after he completed that book’s first draft, which would make it either his fourth or his fifth finished novel manuscript.

The Running Man was written in the “winter of 1971,” which some sources assign to the period between Christmas and New Year’s Day. King remembers writing it during February vacation, which would place it in February 1972.

The Running Man was written in the “winter of 1971,” which some sources assign to the period between Christmas and New Year’s Day. King remembers writing it during February vacation, which would place it in February 1972.

Sources generally say that King wrote the novel in a weekend or, more specifically, over a period of 72 hours. In a 2013 interview in The Guardian[1], King says he wrote it in a week. “I was white hot, I was burning. That was quite a week, because Tabby was trying to get back and forth to Dunkin’ Donuts and I had the kids. I wrote when they napped or I would stick them in front of the TV. Joe was in a playpen. It seemed like it snowed the whole week, and I wrote the book.” As with the other novels from that time, King says it was written “by a young man who was angry, energetic, and infatuated with the art and the craft of writing” in a “Bachman state of mind: low rage and simmering despair.”

Bill Thompson had recently rejected Getting it On (aka Rage). The Kings were living with their two children in a trailer in Hermon, Maine while he taught high school English at the Hampden Academy. Thompson also rejected The Running Man, so King sent it to Donald A. Wollheim at Ace Books. Three weeks later the manuscript was returned to him with a rejection letter King called both cordial and frosty. “We are not interested in science fiction which deals with negative utopias,” Wollheim said. “They do not sell.”[2] King grumbled that the novels of George Orwell and Jonathan Swift seemed to sell pretty well as he consigned the manuscript to the trunk.

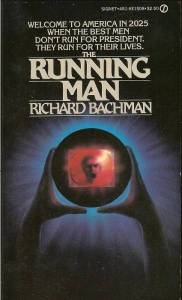

The Running Man became the fourth and final paperback original Richard Bachman novel in May 1982. Again, there is some controversy on this point: some sources say the book vanished from the racks within two months, whereas others claim it was still in print when the Bachman pseudonym was exposed two years later. Others claim it was The Long Walk that was still in print at that time, which is more likely the case.

It also isn’t clear exactly when The Running Man was optioned to be made into a film, but the fact that it is listed as being “based on the novel by Richard Bachman” lends credence to the theory that it was optioned based purely on the story and not because it was a Stephen King property. Christopher Reeve was originally cast as Ben Richards, but was ultimately deemed to be insufficiently bankable. King found it laughable that Schwarzenegger was cast as the novel’s “scrawny, pre-tubucular protagonist.”

Shortly after The Running Man was published, King was asked point-blank whether he was Richard Bachman. According to the interviewer, Signet had confirmed this “popular rumor.”

King’s response: “No, that’s not me. I know who Dick Bachman is though. I’ve heard the rumor. They have Bachman’s books filed under my name at the Bangor Public Library and there a lot of people who think I’m Dick Bachman. I went to school with Dicky Bachman and that isn’t his real name. He lives over in New Hampshire and that boy is crazy! [laughter] That boy is absolutely crazy. And sooner or later this will get back to him and he’ll come to Bangor and he’ll kill me, that’s all. Several times I’ve gotten his mail and several times he’s gotten mine. He’s at Signet because of me and when the editors got shuffled things might have gotten confused. Maybe that’s how it got all screwed up and the rumor started. But I am not-not-Richard Bachman.”[3]

In “Why I Was Bachman,” King says The Running Man may be the best of the first four Bachman novels “because it’s nothing but story—it moves with the goofy speed of a silent movie, and anything which is not story is cheerfully thrown over the side.”

The novel’s ending foreshadows real-world events that would take place two decades after the book was published and three decades after it was written (King states in one interview that it was published with virtually no changes to his original manuscript). Crashing a hijacked plane into a skyscraper is, according to King, the Richard Bachman version of a happy ending.

[1] Stephen King: on alcoholism and returning to The Shining, Emma Brockes, 21 September 2013.

[2] Rotten Rejections: The Letters That Publishers Wish They’d Never Sent, edited by Andre Bernard. Note that many sources erroneously associate this rejection letter with Carrie.

[3] “Has Success Spoiled Stephen King? Naaah.” by Pat Cadigan, Marty Ketchum and Arnie Fenner. Shayol Volume One. Number Six. Winter 1982.

another good essay. Thank You BEV! By why did it take so long to post? I forgot about this project 🙂

Thanks! I was waiting for the other essayists to be ready. We try to keep the posts for a single book close

Well written, and very informative, I didn’t care much for the Bachman Books, Thinner was alright. A few years ago I happened across Blaze, and though most of my friends think it’s a simple book, not to interesting, I thoroughly enjoyed it. Keep up the great work.

Awesome… Great to see more new posts for this feed. Looking forward to following Richard through his reading journey. I read every one, and Of Course anything posted by Bev. Thanks guys…

Informative and entertaining as always. Thanks Bev. This story still awaits the proper cinematic treatment. Eerie to read this now in light of ral world events. King’s prescience is never more unsettling than in this tale.

Another great job, Bev. I love getting all this info; and I love the Bachman books, especially THINNER.